Columbia (STS-107)

In Memory

S

S

STS-107 crew

(seated, l-r) mission

commander Rick D. Husband; pilot William C. McCool

(standing, l-r): mission

specialists David M Brown; Laurel B. Clark; Kalpana Chalwa; Michael P.

Anderson;

payload specialist Ilan

Ramon (Israeli Space Agency)

Oh, I have slipped the surly bonds

of earth and danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings; sunward I’ve

climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth of sun-split clouds – and done a

hundred things you have not dreamed of – wheeled and soared and swung high

in the sunlit silence.

Hov’ring there, I’ve chased the shouting

wind along, and flung my eager craft through footless halls of air.

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue I’ve topped the windswept heights

with easy grace where never lark, or even eagle flew.

And while with silent, lifting mind

I’ve trod the high untrespassed sanctity of space, put out my hand, and

touched the face of God.

“High Flight”

John Gillespie Magee, Jr.

1941

Like everyone in my generation - including

the crew of Columbia - I grew up on the Space Program. Born

in 1961, I was just old enough to remember (if not really understand) the

Apollo 1 Tragedy (1967) that claimed the lives of Gus Grissom, Ed White,

and Roger Chaffee. I remember being roused out of bed to see the

grainy black-and-white images transmitted from the Eagle at Tranquility

Base that historic July 20 in 1969. Thanks to my parents and interested

and sympathetic teachers, I'm fairly certain I saw all of the Apollo launches

and most of the missions' splash-downs on television at home or in my elementary

school classrooms. I fondly remember that each new mission sparked

the imaginations and absorbed the conversations of me and my friends.

I agonized along with the rest of the world over Apollo 13's safe return

and cheered myself hoarse when they made it back safely. I marvelled

at the color television pictures of the Lunar Rovers bounding across the

moon's surface during the latter Apollo missions.

When the decision was made to scale-back

space exploration after Apollo 17, I managed to remain interested. Skylab,

Apollo-Soyuz, the

Vikings, theVoyagers - I followed all of

them. Ah, but the Shuttle Program hooked me from the start.

I skipped work to rush out to Andrews Air Force Base to see Enterprise

piggy-backed on a 747. I followed the first few Shuttle missions

religiously. I swore that one day I'd make it down to Kennedy Space

Center to see a launch in-person. Unfortunately, as other things

preoccupied me (grad school) and as the Shuttle Program's very success

made each ensuing launch seem more mundane, like most people I began to

take the Shuttle Program for granted. The Challenger Tragedy

in 1986 wrenchingly brought my attention back to the program for a time,

but as mistakes were amended and the program once again became predictably

dependable, I drifted away. Ironically, the less I paid attention

to Shuttle missions, the more I came to depend on the work the astronauts

were doing.

As a geographer with training in remote

sensing, I used Apollo photographic imagery of the earth and satellite

imagery from the various generations of Landsat. Yet, throughout

the 90s I came to rely more and more on the quality, number, and human

touch of imagery from Shuttle missions, especially in my teaching.

I use countless images of the earth as seen from the Shuttle in Power Point

presentations to illustrate important concepts in geomorphology, climatology,

and cultural and economic geography for my students. Of course, the

temptation is to look on Shuttle mission imagery as "product" and to forget

that there is a highly-trained man or woman behind the lense of the camera,

floating in weightlessness at a Shuttle's view ports, waiting for the right

shot to pass underneath. The mission specialists aboard STS-107 were

just such men and women. As part of their mission goals, they trained

for long hours on the best digital video and still cameras and took some

stunning imagery of the earth environment (as the images below attest).

Until tragedy strikes, we tend to forget that such a seemingly simple task

as gathering images from the Shuttle platform is part of a very dangerous

job. I didn't personally know any of Columbia's crew, but

I feel a bond with all of them nonetheless. Each of the crew members

of STS-107 knew the risks they were taking, yet took the gamble and gladly

signed-on to take the greatest ride that the modern world has to offer.

Does that make them heroes? They probably wouldn't think so.

They were the best Western Civilization and American and Israeli culture

have to offer. They reached the pinnacle of achievement in their

chosen field of endeavor. They died satisfying their fondest desires,

doing what they loved. Would I have made the same choice they did?

In a heartbeat.

- David S. Hardin

(l) Moonrise through earth's

atmosphere; (r) Grand Canyon tributary

Columbia (OV-102)

Background

Columbia, the oldest orbiter in

the Shuttle fleet and the first to fly into earth orbit in 1981, was named

after the Boston, Massachusetts-based sloop captained by American Robert

Gray. On May 11, 1792, Gray and his crew maneuvered the Columbia

past the dangerous sandbar at the mouth of a river extending more than

1,000 miles through what is today south-eastern British Columbia, Canada,

and the Washington-Oregon border; the river was later named after the ship.

Gray also led Columbia and its crew on the first American circumnavigation

of the globe. Other sailing ships have further enhanced the luster

of the name Columbia: the first U.S. Navy ship to circle

the globe bore that title, as did the command module for the first lunar

landing mission, Apollo 11. "Columbia" was the name applied to the

feminine personification of the United States and was derived from that

of another famous explorer, Christopher Columbus. In the day-to-day

world of official Shuttle operations, Space Shuttle orbiters go by more

prosaic designations; Columbia was commonly refered to as OV-102,

for Orbiter Vehicle-102.

STS-1

April 12-14, 1981

Upgrades and Features

Columbia was the first on-line orbiter

to undergo the scheduled inspection and retrofit program. After it completed

mission STS-40, it was transported on August 10, 1991 to Shuttle contractor

Rockwell International's Palmdale, California assembly plant. The oldest

orbiter in the fleet underwent approximately 50 modifications, including

the addition of carbon brakes, drag chute, improved nose wheel steering,

removal of development flight instrumentation, and an enhancement of its

thermal protection system. The orbiter returned to Kennedy Space Center

on February 9, 1992 to begin preparing for mission STS-50 in June of that

year. On October 8, 1994, Columbia once again was transported

to Palmdale California for its first Orbiter Maintenance Down Period (OMDP).

On September 24, 1999, Columbia returned to Palmdale California

for its second OMDP, during which workers performed more than 100 modifications

on the vehicle. Columbia was the second orbiter outfitted

with the multi-functional electronic display system (MEDS) or "glass cockpit".

Disintegration of Columbia

During Reentry

Saturday, February 1,

2003

Courtesy HO-Reuters

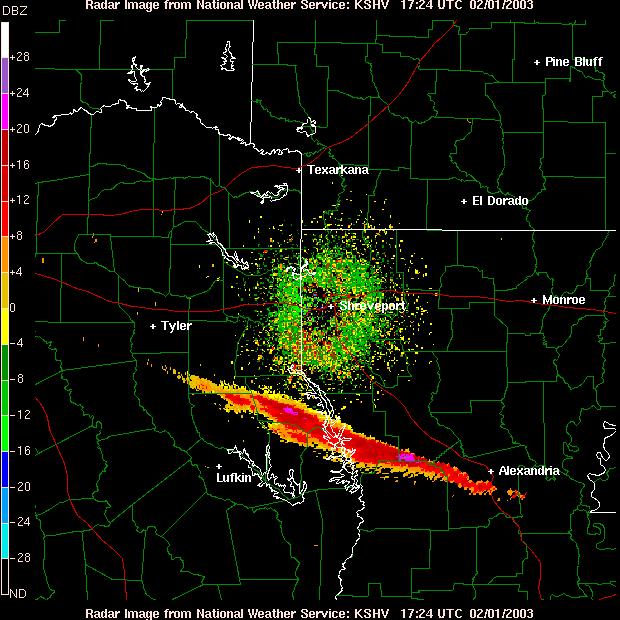

Shreveport, LA doppler radar

images

Radar out of Shreveport,

Louisiana caught Columbia's debris cloud as it crossed the Texas-Louisiana

border. On this animated radar loop (l), the debris appears as a

light blue streak between the labels for Nacogdoches, TX and Natchitoches,

LA. The local radar image for Shreveport (r) clearly shows the extent

of the debris cloud from Columbia between Tyler, TX and Alexandria,

LA

S

S